Abundance Reigns!

The Reminder is a watchword: though it may ascribe a problem to us, the offenders are assuredly others.

RE: "Shinobi and the Art of Criticism" by Garrett Martin

The issuance of Reminders is a tricky business. It presupposes a societal failure, and yet, presumably, will be read by a member of society [how curious!]. If Hollow Knight: Silksong truly "Reminds us that There's Room for Tough Games," or Marvel Rivals "Reminds us that Games Can Be Fun," then you or I'd've somehow forgotten that games can be tough or fun. But the Reminder is a watchword: though it may ascribe a problem to us, the offenders are assuredly others. "We" [air quotes] have a problem, and "some of us" [aggressively gesturing] could stand to be reminded of a thing or two. This naturally makes The Reminder the stock-in-trade of the commentariat, for whom its totalizing rhetoric can belie what are often actually petty, brunching-set grievances. And no doubt it helps that the Reminder hews conservative: it seeks a return to some preferable earlier state, or admonishes society for the erosion of ostensibly traditional values.

When it comes to a new-ish medium like video games—relatively short on tradition...and, well...values—that conservative quality can be subtle, I admit. But that doesn't mean it's not there. By way of example, and to paraphrase some recent secondhand discourse: to argue that "Clair Obscur: Expedition 33 Reminds us that JRPGs are best when they're turn based," would be a kind of genre irredentism (with a dash of essentialism and orientalism), which is an inherently conservative impulse. The rightward vector is there—even if it's diminutive, even if it's about how best to kill fake monsters with giant swords.

Most recently, "Shinobi: Art of Vengeance is here," we're told, "to remind us that there are still games that want it to be 1990 again, when technology and the commercial concerns of a smaller, more rigidly defined audience limited the narrative scope and ambition in presentation that a game could strive for."[[1]]

Art of Vengeance, which I've been playing a bit myself, is in many ways a throwback. It's short on preamble, heavy on arcadelike challenges. It establishes its revenge plot within minutes; the villain's evilness and the imperative to defeat him are considered self-evident. As Martin aptly puts it: "It’s about jumping and running and slashing and slaughtering endless streams of ninja soldier demons who are just as likely to be an evil magical being from another universe as they are an army man with a gun but who have no discernible personality or backstory to speak of regardless." While none of this sounds exactly bygone to me (especially if you wander into the less commercially viable neighborhoods of the digital storefronts) it's Martin's use of the game as an object lesson that I take issue with. As he goes on to write, Art of Vengeance is "a forceful reminder of how games need to be approached and discussed on their own terms."[[2]] And what are those terms? That the game "defies a thoughtful, astute, culturally informed critique about its themes and message because it intentionally represents video gaming at its most primordial and most purely physical." It is a video game, in a word, "about doing, not thinking or feeling."

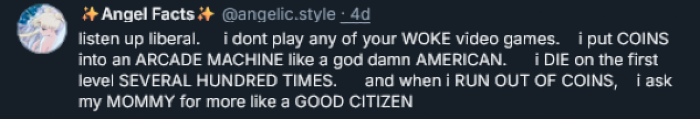

Let me say something that risks sounding like a bad faith/paranoid reading on my part, at this juncture: there is an unfortunate proximity here to "facts don't care about your feelings" that is, if somewhat coincidental, at least a bit itchy, just as the reminder that "there are still games that want it to be 1990 again" inevitably carries with it an unpleasant echo of MAGA. There is a tremendous difference of degrees between these things, of course. But the vectors point in the same direction, an alignment of reactionary sentiment that just happens to transmit through the medium of language. There's the shared demarcation between the cold logic of action and squishy, compromised intellectualism. The mutual foreclosure on appraisals from without, and the unsubstantiated assertion that sometimes, the old ways are best.

Martin again:

"There’s a strand of belief in certain quarters that games writing is insufficient when it doesn’t serve as deep, nuanced critique. That we as a culture and games as an artform have moved past the need for a focus on mechanics and writing about how a game is played instead of what it’s trying to say or how it tries to say it."

It's a little unclear to me, semantically, whether the first instance of "writing" here refers to writing about games or within them, but I don't think this statement is true regardless. I don't think there's a single person who believes this, let alone enough to form a strand (two people, I suppose). It also presents a false dilemma: why should a focus on mechanics necessarily preclude "deep, nuanced critique"? I consider myself about as strident a supporter of literary games criticism as anyone (this is not saying much, there are like 6 of us—so, 15 potential strands?), and as far as I've ever been able to tell its practitioners have always approached mechanics just as readily as message. And why wouldn't they? Mechanics—the simulation of force and motion, the physical manipulation of a system, whatever have you—are a writer's playground. Geometries and spaces and textures and frictions all there, all the stuff "they should have sent a poet" for, wanting only for a describer. This becomes all the more clear if we step outside of video games. It's why sport, to name one notable example, has always been a muse, and for all its kinetic logic, certainly never separate from the cultural or political.

So why this intervention? In short: to forestall other readings. "Action"—to the exclusion of all else, Martin says—"is why you play a game like Shinobi: Art of Vengeance":

...It’s why the game exists. And it’s not something that can really be understood or explained through cultural criticism adjacent to the kind used to analyze movies, books, TV shows, or even narrative-focused games. Art of Vengeance is about how it feels, not how it makes you feel, and that purity and simplicity can be just as powerful and important today as it was when a game’s story was nothing more than fuzzy white block text on a stark black background.

How such a game feels to play, though, has always been inextricable from how it makes you feel. This why Ajay Singh Chaudhary could write that DOOM (2016), another artifact from that era dug up and refashioned (and one even more blatantly disinterested in standing on ceremony) is about asking "how do you feel?" It's how Martin can refer to Art of Vengeance's evocation of gaming in the 90s, already a few decades removed from the birth of the medium, and by then sporting the mutated, neon outgrowths of so much child marketing, as "primordial."[[3]] To casually dismiss those trappings as shorthand and drill-down singularly on mechanics requires fluency with the aesthetics of action figures (and the cartoons and video games produced alongside them in the name of vertical integration) that Art of Vengeance is invoking. Comfort, in other words, is both experiential and something to be experienced. The very ability to "shut one's brain off" signals a kind of privilege, if only a momentary one.

But of course, it's never enough to only shut one's own brain off. If others are out there insisting, obnoxiously, on ongoing thought, they might someday harsh the vibes. And so when Martin writes that this is not a game about "thinking" or "feeling," he is compelled to also add that action alone "should represent the sum totality of any discourse around the game" (emphasis mine). Who does that serve? Not readers. Certainly not critics.

Where the literary criticism he denigrates is additive, open-ended, malleable [read: squishy][[4]], Martin's by contrast is rigid, conservative. It states that there are some things that are good in one narrowly understood way—the author's—and it seeks to wrench that subjective opinion away from its place amid the perpetual skirmishes of intellectual consideration & reconsideration, and to elevate it to the mantle of unquestionable truth. This is the self-appointed purview of the rightist thinkers who, as Gareth Watkins recently put it, "struggle to come to terms with a contradictory world that does not conform to their pre-decided categories. They want to assert, simultaneously, that unambiguous laws govern all aspects of being, while acting as though 'truth' is whatever they want or need it to be at any given moment." Old lit-games-crit heads will recognize, in that, the historical canards about the need for "objective" reviews, or myriad similar arguments. Heck, it's enough to almost make a games critic feel weirdly proud: who could be better equipped for reactionaryism than our gamers? They have a front seat to the tech avant garde and are nevertheless acutely sensitive to anything that might remind them they aren't 14 anymore.

The cognitive dissonance can beggar belief. "What is there to be found about life," Martin goes on to ask, "or the human condition, within the jump of a platformer? The repetitive slash of a virtual blade?" As though these only most recent of chores were somehow beyond the scope of intellectual consideration.[[5]] But to answer seriously: much, I think, both specifically and insofar as those things are synecdoche for all video game verbs. Simply witness the way Martin himself describes Art of Vengeance's jump: "It’s a well-ordered jump, with noticeable weight and a reliably predictable arc, and yet overly responsive to midair lateral movement and with a few distinctive rhythms that will lead to frequent mistakes." That is—and I don't say this lightly—Melville-esque writing. It speaks to deep grains of experience, the kind that might, say, equip a person to write an entire chapter about the various qualities of rope.[[6]] I know a little bit more about Martin's life (and my own in reflection) for the simple fact of his having written it. He is thus, ironically, disproving his own point.

Culture and politics consecrate our works from conception. Port such works to modern times, and they do not simply rest on their old cultural laurels, but are instead reinformed by contemporary context, as we well know. The desire to revisit a thing like Shinobi alone is suffused with meaning. "There’s nothing empty about Shinobi: Art of Vengeance’s steadfast belief in classicism," says Martin, and I would tend to agree: there's certainly nothing inert about a steadfast belief in classicism.[[7]] But it doesn't matter whether the game itself vocalizes a message or not. There's a quote I recently encountered from Wim Wenders, the film director, that I think neatly boards up any hidey-holes people might use to disavow these stakes:

Every film is political. Most political of all are those that pretend not to be: entertainment movies. They are the most political films because they dismiss the possibility of change. In every frame they tell you everything's fine. They are a continual advertisement for the way things are. - "The Logic of Images"

We find ourselves, though, in a moment in which it's already impossible to dismiss the changes happening all around us. We can feel the tide pulling around our ankles, dragging us backwards as we speak. We see the desperate pleas to not obey in advance, and hear our right-wing governments, exultant as they describe the the various ways in which they're reversing decades of progress on everything from environmental protections to medicinal science. Indeed, there are some people who want to make it 1890 again.[[8]]

This goes some way to explaining why I find the Reminder's smarmy admonishments so grating. Who could possibly forget the recent past when we're having our noses rubbed in it all the time? Not only by policymakers, but by workaday grifters and rubes churning out reams of uncanny decade slop and hearth-lit Kincade-bait:

Nostalgia is of course, as these images make thuddingly obvious, always being actively constructed in the present. It's a retcon—who really misses an early 'aughts Wal-Mart? Most people that I know see the dissonance and laugh. But amidst the feeding frenzy and constant churn of social media, fissures are opening up anyway. For example: what my memory tells me is that when literary critics last dared set foot in mainstream gaming spaces, they—and particularly the womenfolk among them—got run out of town with torches and pitchforks. And yet I keep encountering this sentiment that the field is just now finally getting back to some sensible reality, after years of domineering by those same critics.[[9]] It's no coincidence, I think, that the rise of this sentiment corresponds with the moment the critical sector seems to truly be singing its swan song. Akin to the U.S. government's forthcoming elimination of the Bureau of Labor Statistics, or the same for food insecurity data collection, because it doesn't like their reports (and because we cut SNAP benefits), or as someone recently put it in a post: "so many dead canaries and we just keep on mining."

What has risen in their stead is a delirious fantasy that this could all be good for us, somehow, that capital, unimpeded, will furnish us with solutions from its own wallet. The notion finds its face in Abundance theory, as proffered by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson, which poses solutionism to a variety of social ills, from climate change to housing shortage. Yet Abundance neglects the fact that the period of our greatest standard of living corresponded with our strongest union participation. It elides the intransigent position of consolidated corporate interests like the fossil fuel lobby, which will need to be confronted and defeated if we're to survive at all. Its utopian vision of the America of 2050, divorced as it is from the hard, ugly work required to get from here to there, is tantamount to all that AI slop of the past (AI, naturally, features prominently in how Klein and Thompson seek to reach that utopia, not entirely unlike DOOM 2016's conceit of mining hell for profit). But there is no lifehack; nobody is exempt from the work, or the moral imperative.

As right wing authoritarianism sweeps the field, profiteers and copers alike seek to nail down what they can. To the former go the actual spoils, the latter the cosmetic and immaterial, the "ephemera of late capitalism." Neither are desirous to hear from any Cassandras as they scuttle about doing so. As Pauline Kael noted, "without a few independent critics, there’s nothing between the public and the advertisers,” and the public has perhaps never been so apathetic to the prospect. But it's the critic's "uninhibitedly opinionated expression" that intercedes on its reader's behalf. This is the literary quality that can't be abandoned, the part that teases the cultural significance out from even those works that would disavow it if left to their own devices, the better to continue reaping profit. As Richard Brody recently put it: even as such criticism "confronts a work’s commercial role, it also embodies the opposite—a work’s potential vastness, the possibly overwhelming and transformative impact of a single viewing or listening." Spurning "such essentially literary explorations of art," he continues:

...as the Times seems ready to do, is a disservice to readers and to art itself. In downgrading reviews, publications yield to the temptation of corporatized impersonality, just as much as tightly formatted and studio-governed Hollywood movies do. Arts coverage risks becoming a spectacle unto itself, the creative vitality of individual voices replaced by a smorgasbord of packaged samples.

This, he writes, would represent "a faux expansion that would actually be a grave diminution." A theory of Abundance to replace the critic's populism, and something I seem to be encountering daily, in this field. I read each subsequent entry into this growing, sarcastic litany. It goes like:

Maybe hype is good? Maybe games are just good?? Maybe a difficult industry environment gives me a hall pass for journalistic ethics? Perhaps somehow, in spite of the opportunistic mass layoffs and the broader immiseration of labor, ownership is just voluntarily foregoing the exploitative practices it has historically engaged in at all other times, out of the goodness of their own hearts? Maybe that could be the case for the game I'm most excited to play? Wouldn't that be a relief? Wouldn't that be so much simpler? Maybe it's actually ok to get that bag? Maybe it turns out that the streamlined delivery of cliché is what respecting me looks like? Perhaps if I can be seen sanctioning my own relegation to status-quo-approver, it stops it from representing my own impoverishment, and actually, when you really think about it, maybe it even enobles me? Maybe some games can just be off-limits to literary criticism, and that’s ok? Maybe this could all actually be really beautiful?

This is simply a conservative reeducation from first principles, a series of small self-delusions that seek to reconcile all the various, galling losses stacking up. So many stochastic concessions to the ruling right. But I have more respect for the most black-pilled doomsayer than I do for the ones trying to rationalize it, or using the chaos to surreptitiously land grab and throw up walls around their own petty fiefdoms, or indulging their own long-closeted conservative kinks. By declaring ourselves beyond the trenches of critique, our interests beyond the purview of critics, we are fooling ourselves, proclaiming that by cutting off the spited nose, we have somehow ended up with so much more face.

[[1]]: A couple caveats up front: I have a great deal of respect for Martin, who in his long tenure at Paste Games (now Endless Mode) has always supported bold and thoughtful critics and criticism. And while I believe his argument in this piece to be regressive, I want to take pains to separate that from the person or their politics. When I say that the arguments within it represent a conservative mode of thought, I mean so in the limited sense of a tendency that we all lapse into from time to time, myself included. I'm also going to be extending my counterargument into some broader trends that are out in the ether, and these should not be construed as Martin's, which was only my jumping-off point.

[[2]]: Somewhat aside, I've previously argued, and long maintained the exact opposite stance on "discussing games on their own terms"—I think we as critics tend to be far too deferential to the fairly limited bounds developers and publishers set for their games. Consider how at pains many are to argue that games that are plainly political are anything but as just one very obvious example. But I also think that many reviewers are very happy to take their foot off the gas whenever a game makes a big show of signposting its genre bonafides. I could argue that's in fact what Martin has done with his review—or I would, if I wasn't happy that he actually instead used it as an opportunity to write about criticism itself, thus giving me a chance to do the same.

[[3]]: And what constitutes the primordial ooze of gaming, anyway? As Ed Halter put it, they "arose out of an intellectual environment whose existence was entirely predicated on defense research." Which would make it the sickly, oscilloscope-green of Spacewar!, the diatom fighter ships on the petri dish screen of the PDP-1.

[[4]]: See for example, Richard Brody's defense of the written critical review, which he describes as: "not spreading my arms out in front of traditional reviews to protect them from insult or attack" but rather "advocating for them, not in order to preserve the status quo or to revive past practices but to advance the cause of art itself—because reviews, far from being conservative...are the most inherently progressive mode of arts writing."

[[5]]: Imagine, say, asking Tolstoy what there is to be found about life in the repetitive slash of a wheat scythe?

[[6]]: Chapter 60: "The Line," and naturally, my personal favorite.

[[7]]: I'm not exactly being fair here, I know. I wouldn't pin that conservative baggage on Art of Vengeance itself. But anyone who might see in it some kind of "Retvrn" aspirations, well...

[[8]]: A real banner year for tariffs, I gather.

[[9]]: Just 4 "Likes" on that post. Q.E.D.